Advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI), cloud computing and smartphones are being used in Malawi national-level plant health project to track pests, climate change stressors, and provide advice to farmers.

Modern advanced technology has various uses in many sectors, including agriculture. Plant health is one of the areas in agriculture that is utilising technology such as AI and E-learning in the early detection and diagnosis of crop pests and diseases.

Tracking plant pests and diseases

Crop losses caused by plant pests, diseases and weeds are estimated at 42% worldwide. Such losses have potential of devastating the food situation, particularly for countries that rely heavily on subsistence farming. This is the case for Malawi in southern Africa, where smallholders produce about 80 per cent of the food and 20 per cent of agricultural exports.

NIBIO is leading an international collaborative project in Malawi called Malawi Digital Plant Health Service (MaDiPHS), where advanced AI, cloud computing and smartphones are currently being calibrated to track plant pests and diseases, climate change stressors and provide advice to farmers. This will be part of a digital agricultural plant health services at the national level in Malawi. The system will be a comprehensive platform designed to address plant health challenges and provide timely and accurate information to farmers and all agricultural stakeholders.

However, farming communities and extension systems in Malawi can greatly benefit from implementing digital technologies. The current computing model is based on the PlantVillage model, developed by Penn State University that is extensively used in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Burkina Faso, Nepal and many other countries,

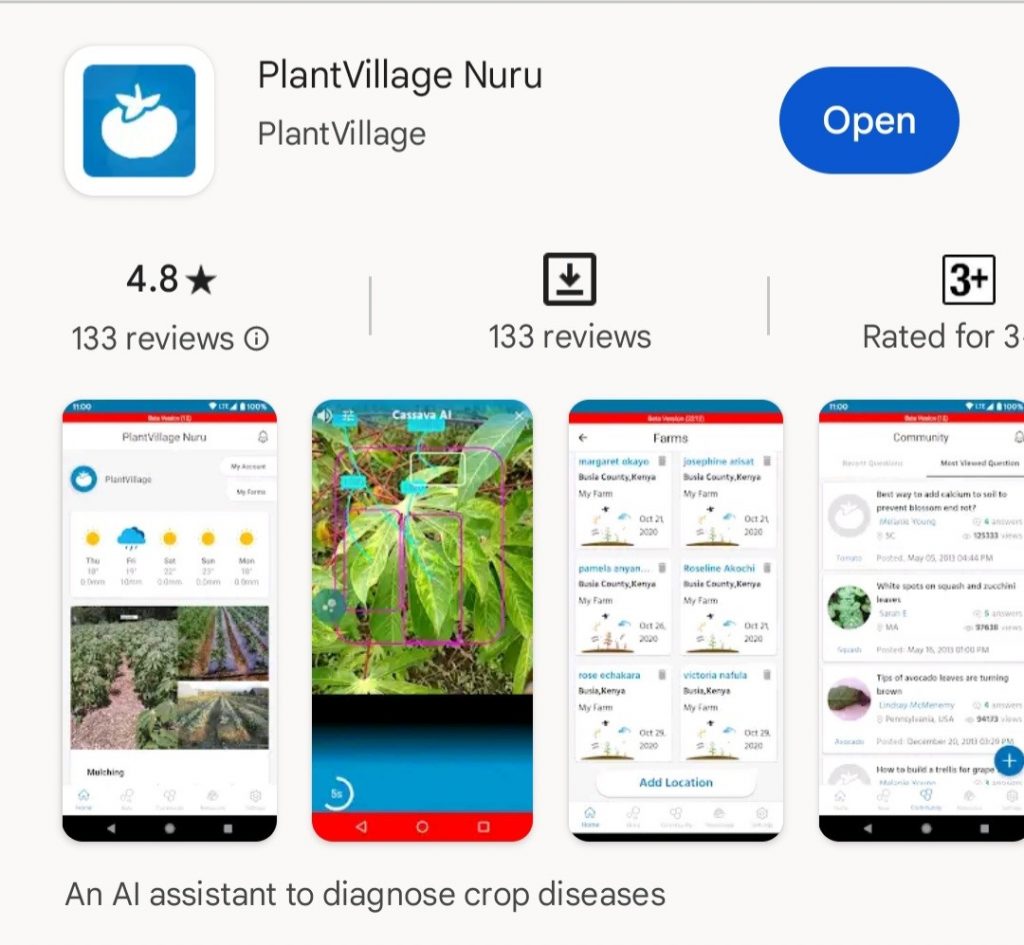

PlantVillage Nuru mobile application

An AI assistant called Nuru is now being adjusted for use within the digital system targeting Malawian crops. PlantVillage Nuru is an Artificial Intelligence (AI) application. Nuru is Swahilli for light. It was created from a deep learning object detection model that can determine the presence of diseases and pests in plants based on foliar symptoms.

object detection model that can determine the presence of

diseases and pests in plants based on foliar symptoms.

Nuru was developed by PlantVillage at Penn State University with the UN, FAO, CGIAR, and other institutions providing technical input. It provides a simple, and robust means of conducting in-field diagnosis without requiring an internet connection. Diagnostic tools that do not require the internet are critical for rural settings, where internet access can be sometimes be limited.

As an AI assistant Nuru has learned to diagnose multiple diseases and pests in cassava, maize, potato, coffee, banana, bean and wheat (among others). Now it is being calibrated to be used in Malawi, targeting the priority crops of the project; cassava, banana, ground nuts, maize and tomato.

“The AI is trained to recognise symptoms when you show an infected plant, pest or disease manifested on the plant. So, what we are currently doing is collecting images to make the app recognise disease symptoms and be adapted to the local conditions in Malawi. Machine learning is continuous – the more data it has, the better it will perform,” says Kelvin Nyongesa, project manager, of PlantVillage Malawi.

Tested and validated by PlantVillage Field Officers

The decision support systems are tested together with end-user groups.

plant health field for tasks such as early detection

and diagnosis of multiple crop diseases and pests.

Photo by PlantVillage

“We have established twenty PlantVillage Field Officers that are working fully with the project, and we will have ten more. As part of the teams, lead farmers are given smartphones with the PlantVillage app, and they use the app daily in the field and give us feedback every Friday. We then use this information to see if the app is working, and adjust the system accordingly. We are basically training the system”, explains Nyongesa.

The Field Teams also consists of extension services and “CABI trained Plant doctors” that are helping to validate the system.

“We have provided the validation teams with laptops. These teams consist of for example pathologists, entomologists, or agronomists. Once we have the system working and data coming in, they are verifying that the app is doing the correct thing. This is part of ensuring that the system is working and that they can rely on it. Capacity building is important, so we are also engaging IT experts to learn about management of the system. This training is important as we want local partners to be able to operate without us when the project is finished, he points out.

“This capacity building actually aligns with our work with the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation to increase the accessibility of national partners to advanced AI systems like PlantVillage,” comments David Hughes from Penn State University.

-”The Nuruapp sends out advice automatically, but this needs to be tailored to meet government Malawian recommendations and end-users needs when it comes to for example language, Nyongesa adds.

Work closely with government

A key priority of the MaDiPHS project is to strengthen national partner capacity for management of the digital service to ensure long term sustainability. In MaDiPHS one prerequisite is that the Department of Agricultural Extension Services (DAES) will produce and approve plant health information provided through the NURU app. This is a very important cooperation”, says Berit Nordskog, research scientist at NIBIO.

– The locally adapted service for Malawi will be managed by the Malawian government and their capacity developed to improve data collection, data management and ultimately coordination of extension messages, she concludes.

Blessings Susuwele is Principal Extension Methodologies Officer at the Ministry of Agriculture in Malawi. He says the results in Malawi are very promising:

“The simplicity and timeliness of having plant health issues sorted is quite remarkable. Farmers are now able to manage plant health issues which at first they were not sure of, and would resort to uprooting. The limitation is the access to smartphones by the majority of smallholder farmers which is on the lower side,” he points out.